I begin with my own collage of pain. This is an impromptu collage of things in my bin and medication cabinet. I don’t consider myself to be a chronic pain patient, though I do have a chronic condition and am in pain a lot. That’s a story for another time. Here is the book surrounded by scraps of the paper, the information leaflet from my medication boxes and the bag from the pharmacy reminding every patient of cancer. There are used tablet packages, bottles, earplugs, and a pair of sunglasses. These are some of the things that pain sufferers typically use. In many of Padfield’s patients’ collages, they use similar items, sometimes to spell out their feelings, or to illustrate the unbearable number of pills they take to control pain.

Deborah Padfield is an artist and chronic pain sufferer herself. After a conversation with her own consultant, she decided to use her art to express how her pain felt to her doctors. This resulted in the projects INPUT and Face2face. Using collages and photographs, Deborah Padfield worked with chronic pain patients to create visual representations of how their pain felt and what it meant to them. Then with their permission and support, these photographic images were made into ‘pain cards’ to be used by doctors in pain clinics to communicate with their chronic pain patients. I first read Deborah Padfield’s book Perceptions of Pain all the way back in January when my tutor Brian Hurwitz heard that I was researching performances of pain and gave me his copy of the book to keep (he also contributed to the book). I was quite moved by this gesture. I then attended a conference at UCL ‘Encountering Pain’ which brought together Rita Charon, Joanna Bourke, and Deborah Padfield amongst other pain specialist, scholars, and sufferers. Deborah Padfield did a talk on how she used her work with pain patients and invited the patients themselves to talk about the art. I also had the pleasure of briefly talking to Deborah during the break. Even though I was only there for a few hours, it was very stimulating and very informative.

The visual language of pain

I have always found it hard to explain my pain to doctors. You have to explain it to them so that they can understand it, and it doesn’t matter how often you try to explain it to them, they still don’t understand. (Rob, in-patient, INPUT, 17)

One of the greatest challenges in diagnosing and treating chronic pain is how to express pain. What does the patient mean by ‘sharp’ pain? ‘Intense’ pain? My 10/10 might be not your 10/10. Other people cannot see your pain. Pain is invisible. Doctors, friends, family begin to question the legitimacy of your pain when that pain doesn’t go away. David Biro, in The Language of Pain, suggests that part of what makes suffering painful is the incommunicability of pain: the inability to talk about pain to the people around you, is what makes pain most painful.

Deborah Padfield’s project aims to give form to pain. Working one-to-one with patients at St Thomas Pain Clinic, INPUT Padfield made a series of photographs and prints using objects that were related to their pain. In processes of deconstruction and reconstruction, the photographs emerged as personal portraits of each patient’s pain.

“By this means, pain sufferers were able to project the private sensations and experiences of pain – its associations, intensities, qualities and significance – outwards on to the publicly accessible surfaces of canvasses and photographic plates.” (Brian Hurwitz, ‘Looking at Pain’, 10)

Visualising pain is not just useful for patients expressing their frustration, it’s useful for doctors too. A visual language of pain allows the doctor to understand the nature and quality of the patient’s pain, and give appropriate diagnosis, as well as empathise with the patient’s suffering. Images of pain break down the distance and ‘wall’ created by pain, and shifts the role of the patient from a sufferer of pain, to the ‘creator’ and master of pain.

The images selected here are ones that I particularly liked for the power of their visual metaphors. Every image is interpreted differently by different people; the point is not so much the absolute objectification of pain but to give a common platform for the discussion of pain, which now becomes public and speakable.

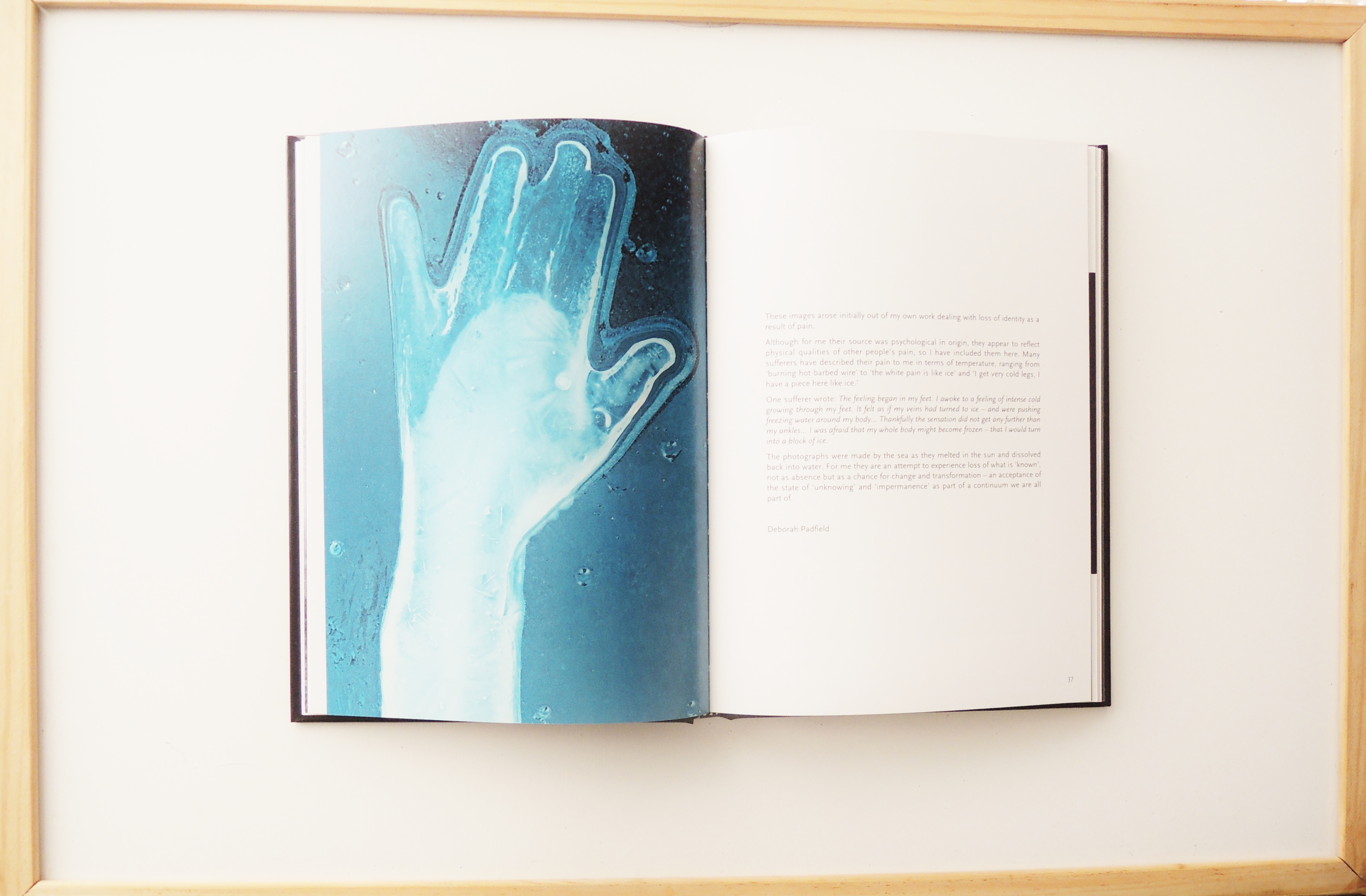

Pain like Ice

This is part of a series of photographs of ice. They were made by the sea as the sun melted the sun into water. For Padfield the image of ice represented a loss of identity as a result of pain. But for others it was a literal representation of icy white pain. The transformations of flesh into ice and ice into water express a state of ‘unknowing’ and ‘impermanence’ that come with the experience of loss. Personally I also felt that the photographs of ice are very beautiful in that the core is always more opaque than the melting exterior. This reminded of the human physiology of bones and flesh.

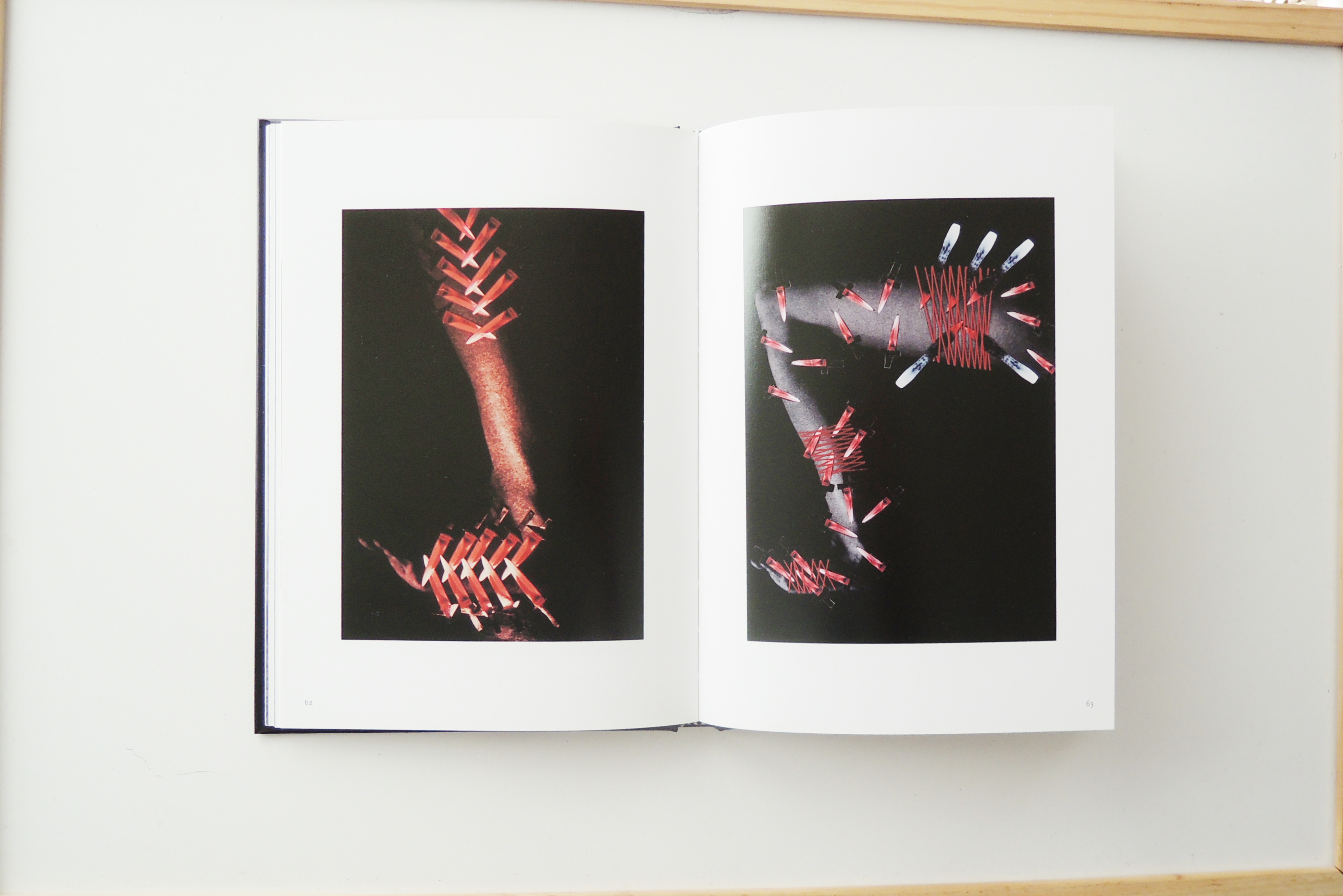

Pain like knives

These are very powerful images on many levels. Not only did the patient feel physical chronic pain, the intensity of the pain and the stress it had on her life made her depressed and mentally exhausted. Chronic pain sufferers tend to be more at risk of mental health problems because of the absence of emotional support from others who fail to ‘see’ their pain. They are deemed scroungers, lazy, malingers because their pain do not come with bandages. The raw redness of the knives represent the mental and physical pain that strike her like ‘red hot swords’. This creates a division of her ‘self’ as one part tries to act normal and the other tries to react to the pain.

“Apart from the physical swords and things, is that there are always two of me. There is the me who is talking to you now, but there is another me, all around, rather like an aura. That is the pain and that is what I’m continually fighting to get out of.” (Frances Tenbeth, 60)

These images remind me of another image (not shown here) of a woman’s self-harm scars. This patient suffered from chronic pain and depression because she felt ignored and that she needed to make her pain ‘visible’. I didn’t want to put an image up because it is quite graphic and might be triggering. This image is of the scars on her left hand and next to the photograph is writing that is shaped around that wrist-shaped white space. The text reads ‘I feel like I’m some kind of alien, I ask for help and people don’t believe that there’s anything wrong with me…The pain is invisible, people think I’m making it up’.

“The idea I had was to photograph the scars on my arm. I had people not believing me and so I became very depressed and self harmed. I have scarred arms – for me that is an important part of this whole process, because that is what pain made me do. It says to me that is how I expressed my pain.” (Helen Lowe, 41)

Together with the knives images, the sense that chronic pain (and pain in general) is never purely physical is something that speaks to many people and which we badly need to recognise.

“I want to show my scars because I know that there must be other people with pain who have felt as desperate as I have. If I stand up and say I have done that it gives other people a chance to say, ‘actually I have felt the same way’. It removes the stigma and the need to cover it up”. (Helen Lowe, 41)

Putting pain into pictures is an act of courage that breaks the boundaries of the physical body. At the conference, some of the patients that worked with Padfield were there to give talks. They spoke of sense of relief creating the images gave, and how being able to express their pain made managing pain easier. Instead of being destroyed by mental and physical pain and destroying the body with self-harm, the construction of pain through images gave them a chance to confront their problems in a productive and meaningful way.

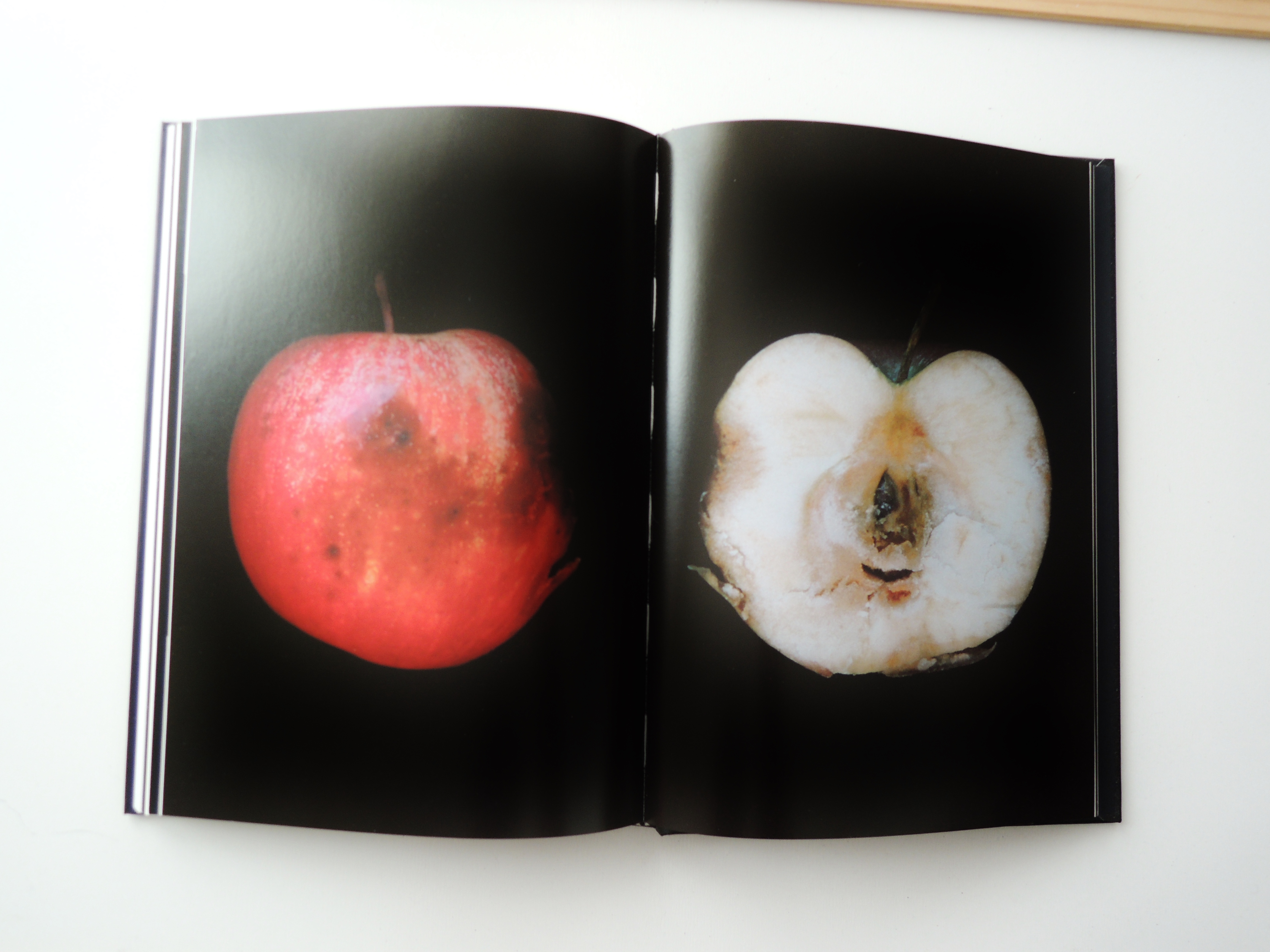

The feeling of decay

The rotten apple is a metaphor for the rottenness of the body in pain. The apple rots from the inside, and only becomes visible as bruises after a while. On the outside the apple, like the sufferer, looks ‘fine’. But once ‘cut open’, the rottenness is revealed.

“Pain […] is like an apple which is rotten from the inside. There is the central core which is the centre of the pain – which is what it would be if it were in the spine – and it comes through and affects the skin. When you have severe pain it increases and increases, so you can imagine that apple going rotten and eventually that would take you up to the peak of the pain.” (John Pates, 103)

The point of this rotten apple metaphor is that pain begins from beneath the surface. The core of the apple, is the spine of the body, the pain receptor-centre. As a figure of speech, a ‘rotten apple’ describes a bad person, whose morality will corrupt the rest of the batch. This metaphor also captures the sense of alienation and rejection that a pain sufferer feels, like a ‘rotten apple’ that doesn’t deserve to bought or sold at the supermarket.

Reflections

Part of what I enjoyed most about the ‘Encountering Pain’ conference was the dialogue between practitioners, doctors, and patients. It wasn’t just talking about pain sufferers, it was talking about pain with pain sufferers. The images that Padfield made with patients were turned into ‘pain cards’ that doctors at pain clinics use in sessions with patients. In one study, it was found that compared to consultations without pain cards, consultations with pain cards created a more equal platform between doctor and patient, where the patient sometimes spoke more than the doctor, thus reversing the doctor’s domination. It gave patients more agency, a tool for speaking about pain and made consultations more effective as well as less sterile. In the future, with more funding, this has the potential to revolutionise the way consultations are conducted.

Deborah Padfield’s project invites us to start conversations about pain, and to try to use imagination to understand other people’s pain. Pain is not as private as we say it is. Whether we successfully describe the pain or not, it is the process of talking that matters. More than anything, the ‘privacy of pain’ has been an excuse for painless people to ignore talking about pain. But pain is something that affects everyone, whether visible or invisible. And the more we talk about pain, the better we will be at it.

Leave a comment